Impact of Hearing Loss and Rehabilitation on the Psychological Well-Being of the Elderly

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Hearing loss in the elderly is a common disorder which range from an undetectable degree of disability to profound alteration in the ability to function in society. Hence, this study was undertaken to assess the impact of hearing loss and rehabilitation on the psychological well-being of the elderly.

Method

Patients above 60 years complaining of hearing loss were evaluated for the otoscopic examination, audiological assessment, psychological assessment Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening (HHIE-S) version, and Global Mental Health Assessment (GMHA) tool. Data was statistically analyzed to determine the relationship between the hearing loss and psychological affection and the benefit after use of hearing aids and rehabilitation.

Results

A total of 60 males and 50 females were taken into consideration. HHIE-S showed a significant relation with the severity of hearing loss in the initial assessment and also after remedial measures. GMHA also showed a significant statistical relationship with the severity of hearing loss after initial assessment and after remedial measures.

Conclusion

The significant relation of HHIE-S and GMHA with the severity of hearing loss suggest that as the hearing loss increases there is a higher probability of an individual having psychological affection causing the social and emotional situational adjustments producing depression and anxiety. It is also concluded that early remedial measures provide substantial improvement in their quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Normal hearing function depends on the mechanical integrity of the middle ear mechanism and micromechanical and cellular integrity of the organ of Corti, homeostasis of the inner ear biochemical and bioelectric environment, and adequate function of the Central Nervous System (CNS) pathways and nuclei. These depend on normal vascular, hematologic, metabolic, and endocrine function as a result, the disease of almost any human physiologic system which affect the CNS, has the potential to affect auditory function.

It is seen that the rate of deterioration tends to increase with age, the timing of onset is variable, with the greatest variability in the middle years (40~60 years) but when a certain amount of hearing loss has occurred (approximately 75~80 dB HL), (Milne, 1977; Milne, 2009) further progression is very slow, particularly in the higher frequencies (Gates & Cooper, 1991). In all likelihood this represents some form of hereditary degenerative process (Alford, 2011, Browning & Davis, 1983) or some alternative process causing Age Related Hearing Loss (ARHL).

ARHL is an extremely common disorder, and it has a spectrum of effects that ranges from an almost undetectable degree of disability to a profound alteration in the ability to function in society (Ciorba et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2021; Dalton et al., 2003; Ellis et al., 2021). It is a known fact that the onset of ARHL is often insidious, and is frequently accompanied by subtle compensatory strategies, hence is often overlooked by physicians and patients.

First signs of ARHL in males may already be evident at an age of 30~39 years, but in females it generally begins a decade later due to many factors. In the early life it has been found that the female neonates show higher amplitude on Transient-Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions as compared to males, similarly females newborns exhibit greater peak amplitudes, shorter Auditory Brainstem Response latencies, and shorter inter-peak intervals compared to males (Nolan, 2020). Studies have also shown the role of estorgen, it has been documented that estrogen has a neuroprotective role and presence of estrogen receptor in cochlea, studies conducted in mice after knocking out the estrogen receptor show impaired auditory function (Nolan, 2020). Despite the different time of onset of ARHL, hearing impairment in the the principal speech band (0.5~4 kHz) is affected in both genders by 60~69 years (Sharashenidze et al., 2007).

Hearing loss is independently associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline over time with significant associations between greater hearing loss and poorer cognitive function (Choi et al., 2021; Ellis et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2013). Social isolation and loneliness, may be the possible factors mediating the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline (Choi et al., 2021; Dalton et al., 2003; Ellis et al., 2021).

Hence this study was undertaken to determine the morbidities associated with ARHL and the psychological impact on the elderly population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

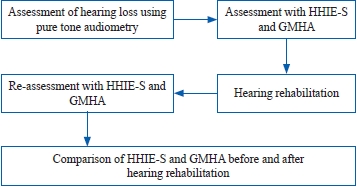

After due approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee of Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, a rural tertiary care institute, with the approval No. 1106, a prospective cohort study of the patients above 60 years presenting with hearing loss was undertaken in the department of ENT. A written informed consent for participation in the study was taken from all the patients participating in the study. The slip outs were excluded from the study. The patients were evaluated and the Otoscopic examination, pure tone audiogram recordings, impedance audiometry recordings and evaluation of psychological affection was done by questionnaire of Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening (HHIE-S) version and Global Mental Health Assessment (GMHA) software. HHIE-S helps to assess the emotional and social-situational adjustments of an individual with hearing loss and the scores were categorized as 0~8 = normal; 10~24 = mild to Moderate handicap; 26~40 = severe handicap (Deepthi & Kasthuri, 2012; Duchêne et al., 2022; Öberg, 2016). GMHA Tool-Primary Care (GMHAT/PC) version is a computerized clinical assessment tool developed to assess and identify a wide range of mental health problems in primary care as it generates a computer diagnosis which can help in the assessment of mental wellbeing of an individual (Krishna et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2010). The patients were also advised appropriate hearing aid devices according to the pattern of the audiogram and then rehabilitation sessions were advised initially for the proper programming followed by familiarizing them with the surrounding environmental sounds. The HHIE-S and GMHA were also repeated after 6 months of use of the hearing device and rehabilitation sessions.

Hearing was reassessed by measuring pure-tone behavioral thresholds with the hearing aids in a sound field. The data was collected and the results obtained were statistically analyzed to derive conclusions.

Objectives of study

The objective of the present study is to determine the hearing loss in patients above 60 years of age followed by assessment of their social and emotional affection using Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening (HHIE-S) and their psychological state by Global Mental Health Assessment (GMHA). Thereafter the patients were advised hearing aids and underwent rehabilitation sessions and after 6 months reassessment was done by HHIE-S and GMHA and the results were compared.

RESULTS

A total of 110 patients were taken into consideration and the results obtained were statistically evaluated using SPSS ver. 22 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Basic details of patients

As per the data collected there were 60 males and 50 females that attended the outpatient department of ENT who were above 60 years of age and with complaints of hearing loss. The highest number of patients appeared in the age group of 60 to 64 years. The socio-economic status was graded in accordance with the Udai Pareekh socio-economic status scale for rural population and the highest number of the patients belonged to the middle class group (n = 50, 45.45%) followed by lower middle class (n = 19, 17.27%) (Wani, 2019).

The otoscopic findings revealed that 51 patients (46.36%) had normal otoscopic findings. Twenty-three patients (20.90%) were having tympanosclerosis with the findings ranging from thickening of the tympanic membrane and various grades of tympanosclerotic patch over the tympanic membrane.

Audiological evaluation took the worst ear into consideration and the average hearing loss was determined by the hearing impairment calculation worksheet of American national standard institute. According to it the monaural hearing loss formula: ([500 Hz + 1,000 Hz + 2,000 Hz + 3,000 Hz] / 4). The patients were categorized according to the severity as summarized in Table 1.

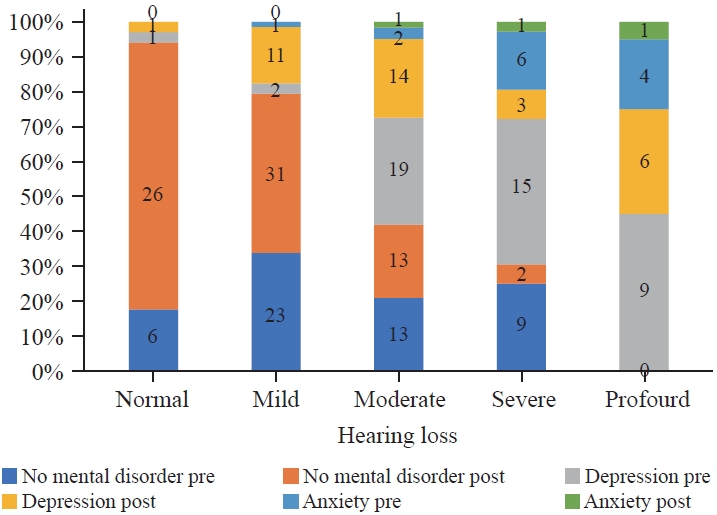

Correlation of hearing loss with (HHIE-S) version (Table 2, Figure 1)

Association of HHIE-S with hearing loss. HHIE-S: Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening.

All the patients under consideration were evaluated by the HHIE-S, the results are shown in Table 2. Taking into consideration the obtained data of severity of hearing loss, a positive correlation was made with the HHIE-S. It was significant to note that highest of the individuals were falling into the category of moderate grade on HHIE-S (59.81%) regardless of the severity of hearing loss. On applying chi-square test for testing relationships between categorical variables, a p-value of 0.001 was obtained which is statistically significant suggesting that HHIE-S correlates well with the severity of hearing loss.

After the use of hearing devices and rehabilitation, it was seen that the patients were greatly relieved and there was a substantial increase in the HHIE-S normal category (from 31.81% before using hearing aids to 66.36% after the use of hearing devices). There was also a statistically significant correlation after applying chi-square test with a p-value of 0.001.

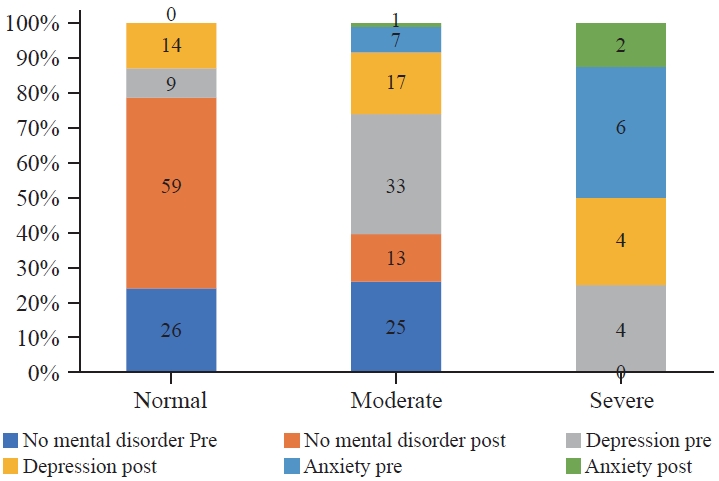

Correlation of hearing loss with psychological assessment GMHA (Table 3, Figure 2)

On correlating the degree of hearing loss with the GMHA it was found that patients in the category of moderate, severe and profound hearing loss are suffering more from depression and anxiety as compared to patients having normal hearing or mild hearing loss as summarized in Table 3 and Figure 3 (Sharma et al., 2004). On applying chi-square test the correlation was determined to be statistically significant (p = 0.001) suggesting that hearing loss has a significant impact on the mental health of an individual.

Association of HHIE-S with GMHA. HHIE-S: Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly Screening, GMHA: Global Mental Health Assessment.

Assessing psychological assessment using GMHA after use of Hearing aid devices and rehabilitation it was determined that there was an increase in the number of patients with no mental disorder (46.36% before using hearing aids to 65.45% after their use). There was also a statistically significant correlation after applying chi-square test with a p-value of 0.0001.

Correlating HHIE-S with GMHA (Table 4, Figure 3)

The two tests that were used to determine the psychological affection in the elderly patients with hearing loss showed statistically significant correlation both before and after use of hearing aid devices and rehabilitation with a p-value of 0.001.

DISCUSSIONS

The highest number of patients were in the age group of 60 to 64 years. Studies have suggested that age is the strongest predictor of hearing loss among adults aged 20~69, the process of decline in hearing starts as early as 20 years of age and gradually progress to the age of 69 with the greatest amount of hearing loss in the 60 to 69 age group. In the present study also, the highest number of patients are seen in the age group of 60 to 64 (Hoffman et al., 2017). According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report 25% of the individuals above the age of 60 are affected by disabling hearing loss (World Health Organization, 2021). Other studies also showed that the prevalence of hearing loss was common in higher age groups in the age limit considered in their study (Choi et al., 2019; Curti et al., 2019; Mäki-Torkko et al., 2001; Pedersen et al., 1989).

The otoscopic examination revealed that 51 patients (46.36%) were having normal otoscopic findings. Twenty-three patients (20.91%) were having tympanosclerosis with the findings ranging from thickening of the tympanic membrane and various grades of tympanosclerotic patch over the tympanic membrane. As our centre caters to the rural population, a habit of cleaning the ears with matchstick or wooden plant stick is common which might be a cause of repeated injury to the tympanic membrane leading to fibrosis and tympanosclerosis. Nineteen patients (17.27%) were found to be having retracted tympanic membranes. A similar study conducted in elderly patients found that 81% were having normal otoscopic findings and 7.1% patients were having scarring or atrophy of the tympanic membrane (Stenklev et al., 2004). Tympanic membrane retraction was related to decreased mobility of the eustachian tube opening in the nasopharynx because of the stiffening of the cartilages in older and elderly patients (Davis, 1990).

On impedance audiometry assessment majority were having normal A type curve (n = 76, 69.09%) followed by B type curve (n = 27, 24.54%). Similar findings were reported in a study that the majority of the patients have normal Impedance Audiometry findings (Stenklev et al., 2004).

HHIE-S is a self-assessment tool containing 10 questions aimed to assess the impact of hearing loss in the emotional and social-situational adjustments of elderly patients and is proposed as a screening tool to determine the social and emotional impact of Hearing Loss (Deepthi & Kasthuri, 2012; Duchêne et al., 2022; Newman et al., 1991; Öberg 2016; Ventry & Weinstein, 1983; Weinstein et al., 1986; Weinstein & Ventry, 1983). In our study, every patient underwent the HHIE-S questionnaire and the scores were categorized as 0~8 = normal; 10~24 = mild to Moderate handicap; 26~40 = severe handicap. In the present study it was determined that the majority of the individuals with normal hearing (85.71%) were in normal category of HHIE-S but as the hearing loss increases to mild, moderate, severe and profound there is an increase in the percentage in the mild to moderate and severe categories. This result signifies that there is a significant increase in social and emotional morbidity with higher degrees of hearing loss affecting psychological well-being of an individual. In a similar study, it was concluded that HHIE-S questionnaire, is suitable in the screening for hearing loss in the elderly as it has high accuracy and user-friendly the quality and there is 10.9% of probability that the elderly with no handicap show a hearing loss, as well as 89.1% of probability that some degree of hearing loss exists in the elderly with a hearing handicap (Servidoni & Conterno, 2018). Studies assessing quality of life in elderly and hearing handicap have documented that there is a significant relationship between HHIE-S score and both social and emotional scores when correlated with each other (Lichtenstein et al., 1988; Servidoni & Conterno, 2018; Tomioka et al., 2013).

The patients were advised of hearing aids. They also underwent rehabilitation sessions and were re-assessed after 6 months. It was seen that there was a substantial increase in the percentage of individuals in normal category, i.e., 26.18% (initial assessment) to 66.36% after use of hearing aids and rehabilitation signifying their importance to alleviate the social and emotional impact of hearing loss in the elderly.

The patients also underwent GMHA and it was seen that majority of the patients were in the category of “No Mental Disorder” but as summarized in the Table 2 it can be seen that as the severity of hearing loss an increases there is increase in the percentage of individuals with depression and anxiety signifying the impact of hearing loss on the mental health of an individual, but after the use of hearing aid devices and rehabilitation there was a substantial increase in the category of “No Mental Disorder” signifying that the use of hearing aid devices and rehabilitation improves the mental health in elderly patients with hearing loss. GMHA has not been compared in any of the studies in PubMed central database but studies have found a significant correlation with the psychiatrist diagnosis and ease of use hence it was used in this study (Sharma et al., 2004).

Finally, a correlation was made between the HHIE-S and GMHA before and after the use of hearing aids. It was determined that in initial assessment as well as after the use of hearing aid devices and rehabilitation, there was a statistically significant correlation suggesting that with the increase in the score of HHIE-S, the score of GMHA also increase. It was determined that there exist a good correlation between HHIE-S and GMHA and if used together can lead to determination of anxiety and depression associated with hearing loss. Though further studies are needed with more sample size to establish their correlation but if both HHIE-S and GMHA are used as a test battery, early determination of psychological impact can be determined and early remedial intervention including hearing aids and rehabilitation can provide substantial improvement in participants’ quality of life.

Through this study, we conclude that there is a significant increase in the affection of psychological well-being of patients with higher grades of hearing loss as determined by HHIE-S and GMHA as both the tests assess the psychological states and show a significant correlation with the severity of hearing loss and also show a significant correlation among themselves and there was a substantial improvement with the use of hearing aid devices and rehabilitation in both HHIE-S and GMHA which is suggestive of psychological improvement and alleviation of social and emotional impact of hearing loss.

Acknowledgements

I thank Naina Kumar, Adhvan Singh and Nutty Singh for their constant support and advice.

Notes

Ethical Statement

After due approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee of Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, with the approval No. 1106, a prospective assessment of the patients of above 60 years presenting with hearing loss was undertaken in the Department of ENT. A written informed consent for participation in the study was taken from all the patients participating in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

There is no conflict of Interest from any authors.

Funding

N/A

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Namit Kant Singh. Data curation: Nikhil Gupta. Formal analysis: Namit Kant Singh. Investigation: Namit Kant Singh. Methodology: Namit Kant Singh. Project administration: Namit Kant Singh. Resources: Nikhil Gupta. Software: Kasagani Veerabhadra Rao. Supervision: Namit Kant Singh. Validation: Kasagani Veerabhadra Rao. Visualization: Namit Kant Singh. Writing—original draft: Nikhil Gupta. Writing—review & editing: Namit Kant Singh. Approval of final manuscript: All authors.