The Efficacy of Cognitive-Communicative Intervention in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is the sign of dementia, and is critical for prediction and preventing its progressions. This study aimed to review literature on cognitive communication intervention of MCI patients systematically, and propose the evidence-based data, including their effect sizes using a meta-analysis method. Thirty-eight researches published since 2012, meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were entered into this analysis. They were analyzed in qualitative aspects, and their effect sizes were calculated in a level of mean and each domain. Outcome measures included the domains of 10 cognitions and 4 communications. The main findings were as follows. Firstly, the general target population for studies was MCI over the age of 50, and intervention programs were designed diversely in a session or mode. Secondly, several domains, including attention, memory, and executive function held a large portion of the intervention programs. Thirdly, the average effect size of interventions was large. Lastly, processing speed and word fluency were very effective and significant among domains in the results of treatment. Current study provides evidence-based information to support cognitive-communication intervention for individuals with MCI. These results also can contribute to diversify intervention approaches and verify their efficacies. Given this, it is possible to facilitate the cognitive-communication intervention for MCI in clinical settings.

INTRODUCTION

경도인지장애(mild cognitive impairment, MCI)는 치매의 전조 증상으로서 진행 상태를 예측하거나 예방하는 데 매우 중요한 함의를 갖는다(Lee, 2020). 예컨대, MCI의 가장 흔한 유형인 기억성 MCI (amnestic MCI, aMCI)는 기억력의 저하가 두드러져 알츠하이머병(Alzheimer’s disease, AD)의 전조 상태로 간주된다(Johnson et al., 2009).

이 같은 임상적 중요성에 근거해, MCI가 일상생활을 저해하는 뚜렷한 병리적 상태는 아니나 신경학적 질환의 발병을 객관적 또는 임상적으로 결정할 수 있는 상태임이 강조되고 있다. 실제로 National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association은 뇌영상 소견 등에 따라 일정 기준을 충족할 경우 MCI 상태에서 AD를 진단할 수 있도록 개정하였다(Dubois et al., 2007). 이밖에 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5)의 ‘경도 신경인지장애’, National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association의 ‘AD에 기인한 MCI’, ‘임상 전(preclinical) 단계의 AD’ 등에 관한 진단 기준(American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Sperling et al., 2011)도 예방적 차원의 MCI에 주목할 필요성을 반영한다.

MCI를 치료하기 위한 의학적 및 약물적 중재와 비약물적 중재는 그 효과성이 지속적으로 검증되고 있다. 특히 비약물적 중재법으로서 다양한 인지-의사소통 전략, 뇌 자극 게임, 생활 양식의 변화(예: 영양, 운동) 등이 권고되는데, 이들은 MCI의 진행을 약화시키거나 늦추는 데 목표를 둔다(Lehert et al. 2015; Simons et al., 2016). 실제로 이러한 중재를 통해 해마(hippocampus), 우측 하두정엽(right inferior parietal lobe), 전두측두 연결망(frontoparietal network), 후두측두영역(occipitotemporal areas) 등이 활성화된다는 보고가 많다(Belleville et al., 2011; Hampstead et al., 2012; Onur et al., 2016).

MCI에 대한 인지-의사소통 중재의 근거로서 인지보존 능력(cognitive reserve)과 인지적 가소성(cognitive plasticity)이 꼽힌다. 인지보존 능력은 기존의 신경 경로나 연결망을 보완함으로써 효율성과 역량을 극대화시키는 능력으로, 신경학적 변화에 따른 뇌의 인지적 변화에 효율적으로 대처하도록 돕는다(Brickman et al., 2010; Lee, 2015). 예를 들어, 인지 훈련은 뇌 부피의 증가 등 구조적 변화를 초래하며, 교육, 정신적 자극, 여가 활동 등이 결합된 지적 훈련은 인지보존 능력을 보다 강화시킨다(Pereira et al., 2007). 이는 노년기의 인지-의사소통 접근에도 유효하게 적용된다. 이러한 인지보존 능력은 인지적 가소성을 전제로 발현된다. 즉 신경학적 변화로 인해 뇌가 위축되기도 하나, 신경세포 및 주변 혈관의 생성, 시냅스 및 연결망의 재형성과 같은 가소성에 따라 뇌가 ‘성장’하기도 한다(Fotuhi et al., 2009). 따라서 인지-의사소통 중재를 통해 새로운 반응 양식을 습득하면 인지적 가소성이 증진된다.

MCI의 중재 시에는 다음의 세 가지 측면을 고려한다(Huckans et al., 2013). 즉 1) 객관적 인지-의사소통 평가에 기반한 경도의 인지적 양상, 2) 일상적 기능 및 삶의 질 평가에 기반한 경미한 기능적 양상으로 독립적 일상생활을 방해하지 않는 정도, 3) 우울, 불안, 피로, 수면장애 등 보편적인 신경정신병적 양상이다. 중재의 초점에 따라 접근법이 상이할 수 있으나, 모든 인지-의사소통 중재는 MCI의 증상을 완화하고 치매로의 진행을 지연시키거나 예방하며 정상적 수준으로의 전환을 촉진하는 데 목표를 둔다. 다시 말해, 회복적이거나 보상적인 접근을 통해 인지-의사소통 기능을 효과적으로 중재한다.

MCI의 중재를 위한 회복적 접근은 신경가소성 기제를 활용해 인지-의사소통 능력을 직접적으로 강화하거나 회복시킨다(Vermeij et al., 2017). 특정 인지-의사소통 과제를 구조적 및 반복적으로 훈련함으로써 해당 영역의 수행력을 향상시키는 데 중점을 두는 방식이다. 반면 보상적 접근은 주로 기능적 측면에 주목하여 인지-의사소통의 결함을 보완하기 위한 개별적인 전략과 능력을 다룬다. 이를 통해 일상적 기능 및 삶의 질에 미치는 부정적인 영향을 최소화하는 데 주력한다. 또 다른 접근법으로서 생활양식적 중재는 긍정적이거나 부정적인 일상 요소를 다룸으로써 위험을 줄이고 방어적 양식을 훈련하는 데 초점을 맞춘다(Bahar-Fuchs et al., 2013; Huckans et al., 2013). 여기에는 인지-언어적 자극뿐 아니라 신체운동, 교육, 동기 부여와 같은 행동 전략 등 다양한 요소가 결합된다. 심리치료적 접근은 이완 운동, 마음챙김(mindfulness) 기술, 인지행동 기술 등을 통해 신경정신병적 증상을 완화하는 데 목표를 둔다. 이 밖에 인지보존 능력을 강화하는 인지 자극 훈련, 다영역적 또는 다양식적 형태의 접근법이 MCI 환자에게 적용될 수 있으며, 방법적 측면에서 인지 자극, 인지 훈련, 인지 재활로 구분되기도 한다(Li et al., 2017).

이 같은 다양한 접근법은 중재 효과의 검증과 함께 발전해왔다. 이에는 중재 효과의 평가 방법, 결과의 정확도, 적절한 평가 도구의 활용 등이 포함된다. 인지-의사소통 중재의 효과를 검토하기 위해서는 1) 중재 전후 인지-의사소통 수행의 변화 정도, 2) 효과적인 중재의 보편적 특성, 3) 임상적으로 진단된 MCI의 결함을 향상시키는 방법, 4) 효과적인 중재 프로그램을 구상하는 데 필요한 핵심적 및 구조적 요소, 5) MCI에 관한 신경학적 과정과 중재를 예측하는 요소 등을 포괄적으로 고려해야 한다(Ellis et al., 2010). 이에 근거해 중재 시 목표로 삼은 인지-의사소통의 하위 영역, 목표화되지 않은 연관 영역, 목표화되지 않고 관련성이 적은 영역 등을 고루 평가한다. 부차적인 영향 요인으로서 교육수준, 직업, 지능 등도 고려해야 한다(Lee, 2020).

인지-의사소통 중재의 효과는 MCI의 신경학적 상태를 예측하고 중재 방향을 고안하는 데 활용된다. 예컨대, 다양식적 중재의 효과는 활용된 전략이 뇌의 초기 연결망(primary network)을 지원하고 새 연결망을 동시에 재형성할 수 있음을 시사한다(Sherman et al., 2017). 반면 미미한 중재 효과는 초기 연결망이 기능 소실, 효율 감소, 탈분화 등으로 인한 부담을 감당할 수 없음을 반영한다. 중재 효과가 없을 경우, MCI로 인해 신경인지적 가소성이 소실되어 초기 연결망과 교류할 수 없고 과제의 요구에 부합할 보상적 기제를 재형성할 수 없음을 의미한다.

중재 효과에 관한 연구는 MCI에서 AD에 이르기까지 다양한 접근법을 대상으로 시도되었다. 결과적으로 인지-의사소통 중재는 MCI의 인지 및 언어, 기능적 의사소통, 일상생활의 기능성을 증진하고 부정적 행동 반응을 감소시킴으로써 전반적인 삶의 질을 향상시키는 데 기여한다는 보고가 많다(Buschert et al., 2011; Huckans et al., 2013; Sherman et al., 2017). 최근에는 MCI를 대상으로 한 컴퓨터 기반 또는 다양식적 중재가 인지-의사소통 기능, 일상적 활동, 삶의 질, 메타 인지(metacognition) 등에 긍정적으로 기여한다는 결과도 제시된 바 있다(Chandler et al., 2016). 그러나 MCI 대상의 중재 접근법이나 프로그램이 다양화되고 개별화되는 추세와 달리, 효과를 검증하기 위한 방법이나 시도는 매우 제한적인 실정이다. MCI에 대한 중재 연구가 지난 20년간 기하급수적으로 급증한 데 반해 증거 기반적으로 효과성을 제시한 연구가 미미한 현실이 이를 반영한다. 예컨대, 뇌영상 기법을 활용해 중재 효과를 살펴 보거나 MCI의 특수성을 고려해 일상생활 기능에 미치는 영향을 평가한 시도는 극히 드물다. 또 치료의 전이 효과(transfer effect)뿐 아니라 중재 이후의 지속적인 유지 효과(maintenance effect)를 분석한 연구도 매우 미흡하다.

이에 본 연구에서는 2012년 이후의 국내외 문헌을 중심으로 MCI 대상의 인지-의사소통 중재 및 효과를 살펴보고자 하였다. 먼저 관련 연구의 질적 특성을 체계적으로 고찰한 후 메타분석을 통해 중재 영역별 효과크기(effect size)를 제시하고자 한다. 질적 변인에는 MCI의 유형, 중재 및 통제 집단의 특성(표본 크기, 연령, 중재 회기), 중재 영역별 프로그램 및 결과 평가 방법이 포함되었다. 양적 변인으로는 인지 및 의사소통의 하위 영역을 분석하였다. 즉 인지는 주의력, 지남력, 처리 속도, 시지각력, 기억력, 작업기억, 주관적 기억력, 추론력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지 등 10개 영역, 그리고 의사소통은 따라말하기, 이름대기, 단어유창성, 언어 등 4개 영역으로 구성하였다. 구체적인 연구 문제는 다음과 같다.

첫째, MCI를 대상으로 한 인지-의사소통 중재 연구의 질적 특성을 제시한다.

둘째, MCI 대상의 인지-의사소통 중재에서 평균 효과크기 및 하위 영역별 효과크기를 산출함으로써 중재 효과를 체계적으로 검증한다.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

문헌 수집

MCI를 대상으로 한 인지-의사소통 중재의 효과를 분석하기 위해 PudMed, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, MEDLINE, Web of Science, EBSCO, OVID, Scopus, RISS 등의 데이터베이스를 활용하였다. 국내의 경우 국내 및 국외 학술지에 게재된 연구를 분석 대상에 포함하였다. 2020년 10월 10일자를 기준으로 2012년 이후 게재된 연구에 한정하였다. 구체적인 주제어는 다음과 같다: 경도인지장애, 인지-언어 중재/치료/훈련, 인지-의사소통 중재/치료/훈련, 중재/치료 효과, cognition intervention/therapy/training, language intervention/therapy/training, cognitive-communication intervention/therapy/training, intervention/therapy effect, mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

논문 선정

본 연구를 위한 논문의 선정 기준은 다음과 같다.

첫째, 연구 설계 방법 측면에서 확률화 배정 연구나 집단 간 비교 연구를 포함하였다. 동일 집단 대상의 반복 측정 연구, 단일사례 연구, 질적 연구, 종설 연구 등은 제외하였다. 둘째, 실험 집단의 연구 대상은 MCI로 국한하였다. 파킨슨병 등 운동성 신경질환, 심리적 증후군, 우울, 암 등 복합 질환이 있는 경우, 주관적 호소, MCI로 진단되지 않은 인지장애 등은 배제하였다. MCI의 하위 유형으로 기억력의 손상 유무에 따른 aMCI 및 비기억상실형 MCI (nonamnestic MCI, non-aMCI), 손상 영역의 단일성을 기준으로 단일영역형(single-domain) 및 다영역형(multiple-domain) MCI를 모두 포함하였다. 실험군은 인지-의사소통 중재를 받은 집단, 통제군은 중재를 받지 않은 집단으로 규정하였다. 셋째, 중재 방법으로서 포괄적 또는 영역별 인지-의사소통 중재를 포함하였다. 음악치료, 미술치료, 심리치료, 예술치료, 융합치료, 신체 운동 등 의학적·심리적·신체적 중재가 결합된 경우는 제외하였다. 넷째, 중재 결과로 인지 및 의사소통 능력을 분석 대상으로 삼았고, 그 외 의학적 및 심리-행동적, 신체적 변화는 제외하였다. 중재 결과에 대한 통계치를 제시하지 않은 경우는 제외하였다.

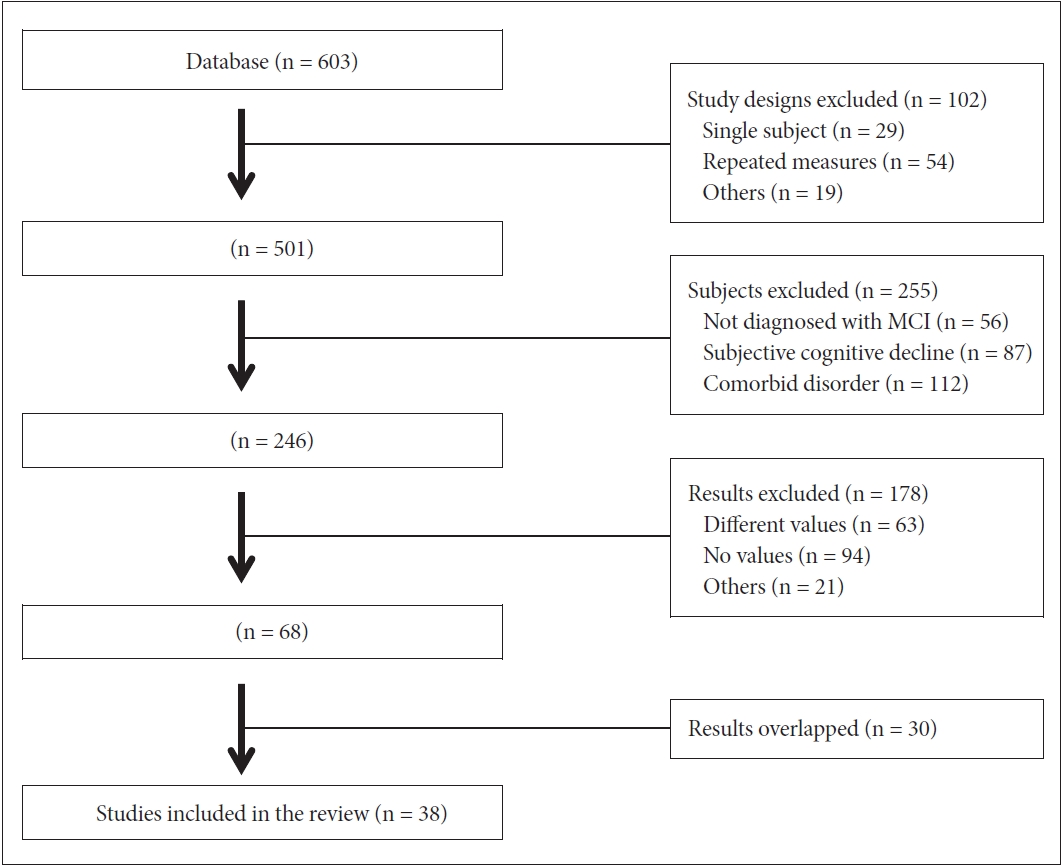

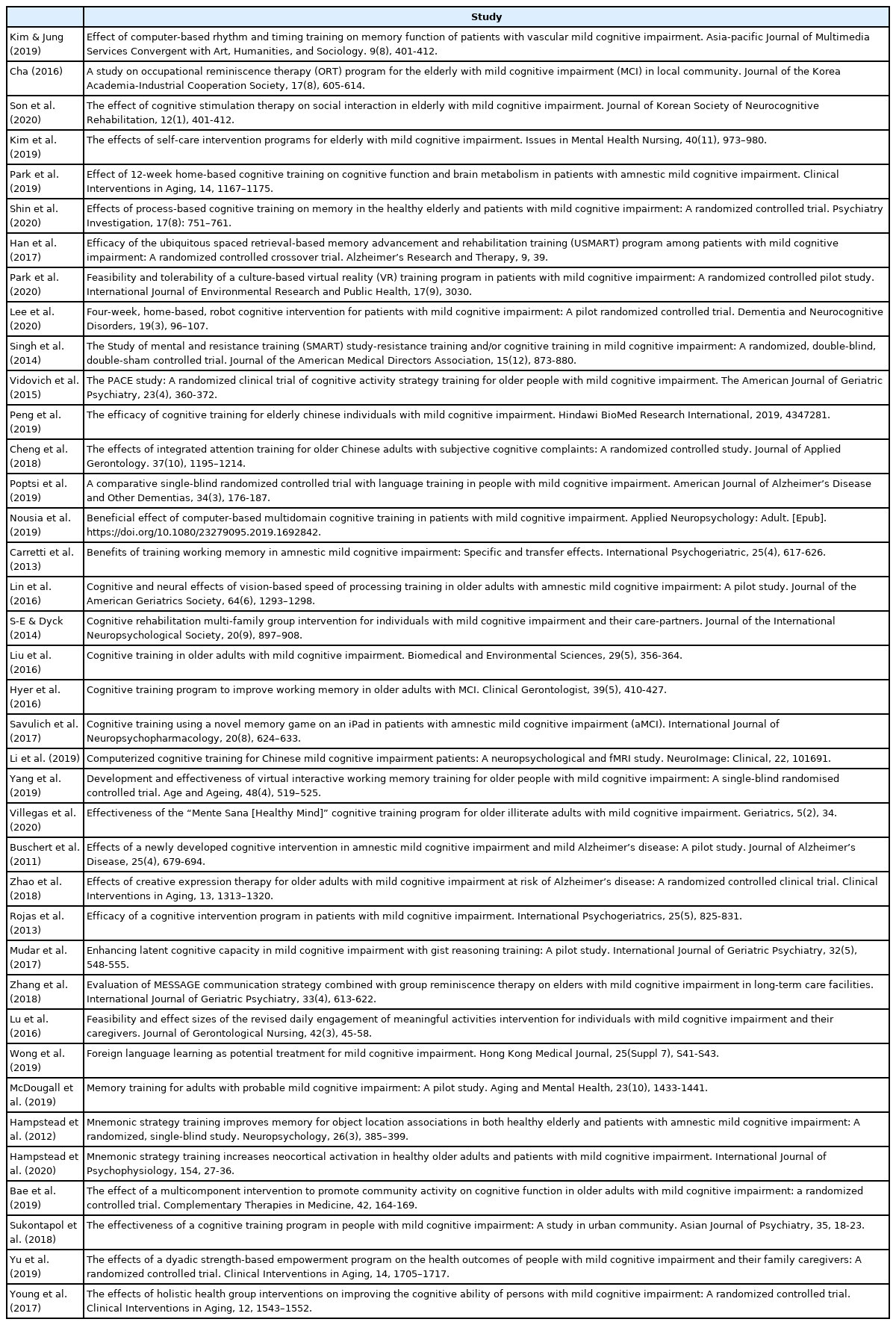

메타 분석을 위해 1차적으로 총 603개의 논문을 선정하였고, 본 연구의 선정 기준에 따라 565개의 논문이 제외되어 최종적으로 총 38개의 논문을 분석하였다. 이 중 국내 연구는 9개, 국외 연구는 29개였다. 논문 선정의 구체적인 과정은 Figure 1과 같다.

자료 코딩

분석 대상에 포함된 연구들은 연구자, 출판 연도, 대상자의 특성, 중재의 영역 및 방법, 중재 결과 평가의 영역 및 방법에 따라 코딩되었다. 중재 결과는 제시된 통계값(mean, standard deviation, t값, p값, F값)으로 분류하여 코딩하였다. 독립변인은 MCI를 대상으로 한 인지-의사소통 중재이고, 종속변인은 중재 후의 인지-의사소통 수행력으로 설정하였다. 1개 연구에서 다수의 중재 결과치를 제시한 경우가 많아, 코딩된 자료의 수는 총 215개였다. 예를 들어, Singh et al.(2014)의 연구는 주의력, 처리 속도, 기억력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지 등 5개 영역에 대한 결과치를 제시하였다. 또 Peng et al.(2019)은 3개 영역의 중재에 대해 주의력, 시지각력, 지남력, 기억력, 추론력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지, 따라말하기, 이름대기, 단어유창성, 전반적 언어 등 다영역적 중재 효과를 제시하였다.

코딩 작업은 언어병리학 교수 1인과 연구 보조원 1인에 의해 실시되었다. 이들은 1급 및 2급 언어재활사 국가자격증을 소지한 자들로 신경언어장애 관련 임상 경력이 7년 이상이었다. 최종 검토 시 이상치나 확인이 필요한 부분에 대해서는 상호 논의한 후 수정하였다.

연구의 질 및 신뢰도 평가

Gersten et al.(2005)의 필수적인 질 지표(essential quality indicators)를 사용하여 3점 척도(1점: 부적절, 2점: 불명확, 3점: 적절)로 연구의 질을 평가하였다. 주요 평가 항목으로는, 연구 대상자의 정보, 집단별 할당 방법, 중재의 절차 및 내용, 실험군에 대한 중재의 내용 및 방법, 중재 목적과 관련된 결과의 측정 등이었다. 38개 논문 중 35개는 평균 3점, 3개는 2.85점으로 평가되어 논문의 질적 수준이 적절한 것으로 확인되었다.

신뢰도를 평가하기 위해 전체 연구의 10%에 해당하는 논문을 무선적으로 선정한 후 2인의 평가자가 각각 코딩하고 효과크기를 산출하였다. 그 결과, 평가자 간 신뢰도는 100%로 산정되었다.

메타 분석

효과크기의 산출 및 해석

인지-의사소통 중재 프로그램 및 결과를 하위 영역별로 분류한 후 각각의 효과크기를 산출하였다. 중재 프로그램의 인지-의사소통 영역은 기억력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지, 언어 등 연구마다 상이하였다. 중재 결과 중 인지 영역은 주의력, 지남력, 처리 속도, 시지각력, 기억력, 작업기억, 주관적 기억력, 추론력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지 등 10개로 분류되었다. 의사소통 영역은 따라말하기, 이름대기, 단어유창성, 언어 등 4개 영역으로 구분해 분석하였다. 중재 효과는 중재 후 측정한 결과값으로 산정하였고, 추후 연구(follow-up) 등 시간의 경과에 따른 반복측정 자료는 분석 대상에 포함하지 않았다.

각 영역별 수행력에 대한 결과값에 근거해 메타 분석용 통계 프로그램인 Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA)으로 평균 및 영역별 효과크기를 분석하였다. 집단의 평균 및 표준편차에 기반해 효과크기인 Hedges’s g값을 산정하였다. 효과크기는 연구 간의 표본 크기를 고려한 가중평균 효과크기(weight effect size)를 적용하였고, 95% 신뢰구간을 기준으로 효과크기의 유의성을 평가하였다.

효과크기를 해석하는 기준으로는 0.20 이하 시 ‘작은(small) 효과’, 0.50 수준 시 ‘중간(medium) 효과’, 0.80 이상 시 ‘큰(large) 효과’로 간주하였다(Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

동질성 검증

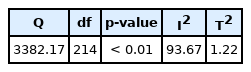

각 연구에서 도출된 효과크기의 통계적 이질성 유무를 확인하기 위해 동질성 검정을 시행하였다(Table 1). 그 결과, Q-df > 0, I2 ≥ 75%로 나타나 연구 간의 분산이 실제로 존재할 뿐 아니라 각 효과크기의 이질성이 상당한 것으로 나타났다(Higgins & Green, 2011). 이에 따라 본 메타 분석을 위해 무선효과 모형(random effect model)을 적용하였다(Borenstein et al., 2009).

출판편의 검증

메타 분석 결과의 타당성을 확보하기 위해 출판편의(publication bias)를 검증하였다(Rosenthal, 1979). 오류의 존재 유무를 알아보기 위해 funnel plot을 확인한 결과 시각적 비대칭성이 관찰되었다(Figure 2). Duval & Tweedie(2000)의 trim-and-fill 기법을 적용함으로써 비대칭성을 보정하였는데, 보정 전후의 risk ratio가 1.24에서 0.97로 감소함을 알 수 있었다(Table 2).

통계적 대칭성을 분석하기 위해 Egger의 회귀 분석(Egger’s regression test) 및 Kendall’s tau 검사를 시행하였다. Egger의 회귀 분석에서 회귀식 초기값(intercept)은 3.77로 통계적 유의성이 있었다(p ≤ 0.01, standard error = 0.78, df = 213.00). Kendall’s tau 검사 결과에서도 연속성 상관 유무 조건에서 모든 tau 값이 0.24로 나타나 통계적 유의성을 보였다(z for tau = 5.17, p ≤ 0.01). 따라서 본 연구를 위해 선정된 문헌들이 출판편의상 오류가 있음을 알 수 있었다.

이러한 오류의 정도를 살펴보기 위해 Orwin(1983)의 안전계수(fail-safe N) 공식을 활용하여 분석한 결과, 안전계수가 989.00으로 대상 연구 수에 비해 누락된 연구의 수가 충분히 큰 것으로 나타났다. 결과적으로 본 연구의 출판편의는 매우 미미한 수준임을 알 수 있었다.

기타 질 검증

연구별 표본 크기 및 분산의 차이를 반영하기 위해 메타분석 시 가중치를 부여하였다. 즉 표본이 크거나 분산이 작을수록 높은 가중치를 부여하여 효과크기를 산출하였다. 이는 분석 결과의 Hedges’s g 및 95% 신뢰구간에 제시되었다. 개별 연구 간 효과크기의 이질성은 I2 값을 통한 동질성 검증 후 무선효과 모형을 통해 보완하였다. 또 표본 크기의 영향은 누적 메타 분석으로 알아보았다. 이를 위해 연구 표본의 크기순으로 전체 효과크기를 분석하고 표본 크기가 전체 결과에 미치는 영향이 미미함을 확인하였다.

RESULTS

질적 분석

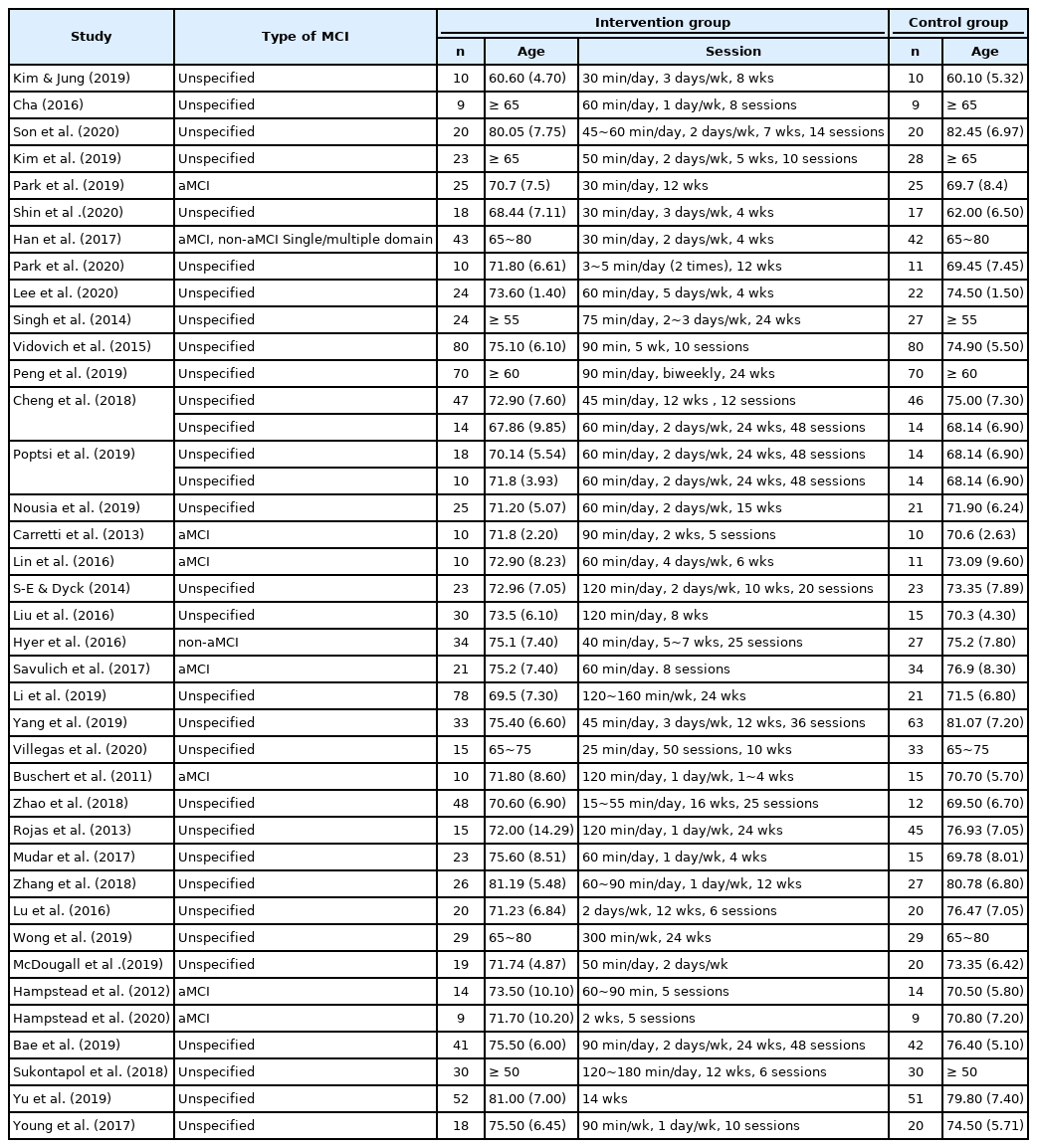

분석에 포함된 모든 연구는 MCI를 대상으로 하였다. 세부적으로는 MCI의 하위 유형을 분류하지 않은 연구가 많았으나, aMCI, non-aMCI, 단일영역형 및 다영역형 MCI로 명시한 연구가 총 9건이었다. 연구에 포함된 대상자 수는 9~80명으로 광범위하였고, 모두 50세 이상의 장노년층으로 구성되었다. 실험 집단에 적용한 중재 회기는 연구마다 매우 다양하였다. 분석된 연구의 세부적인 특성은 Appendix 1 및 Appendix 2에 제시하였다.

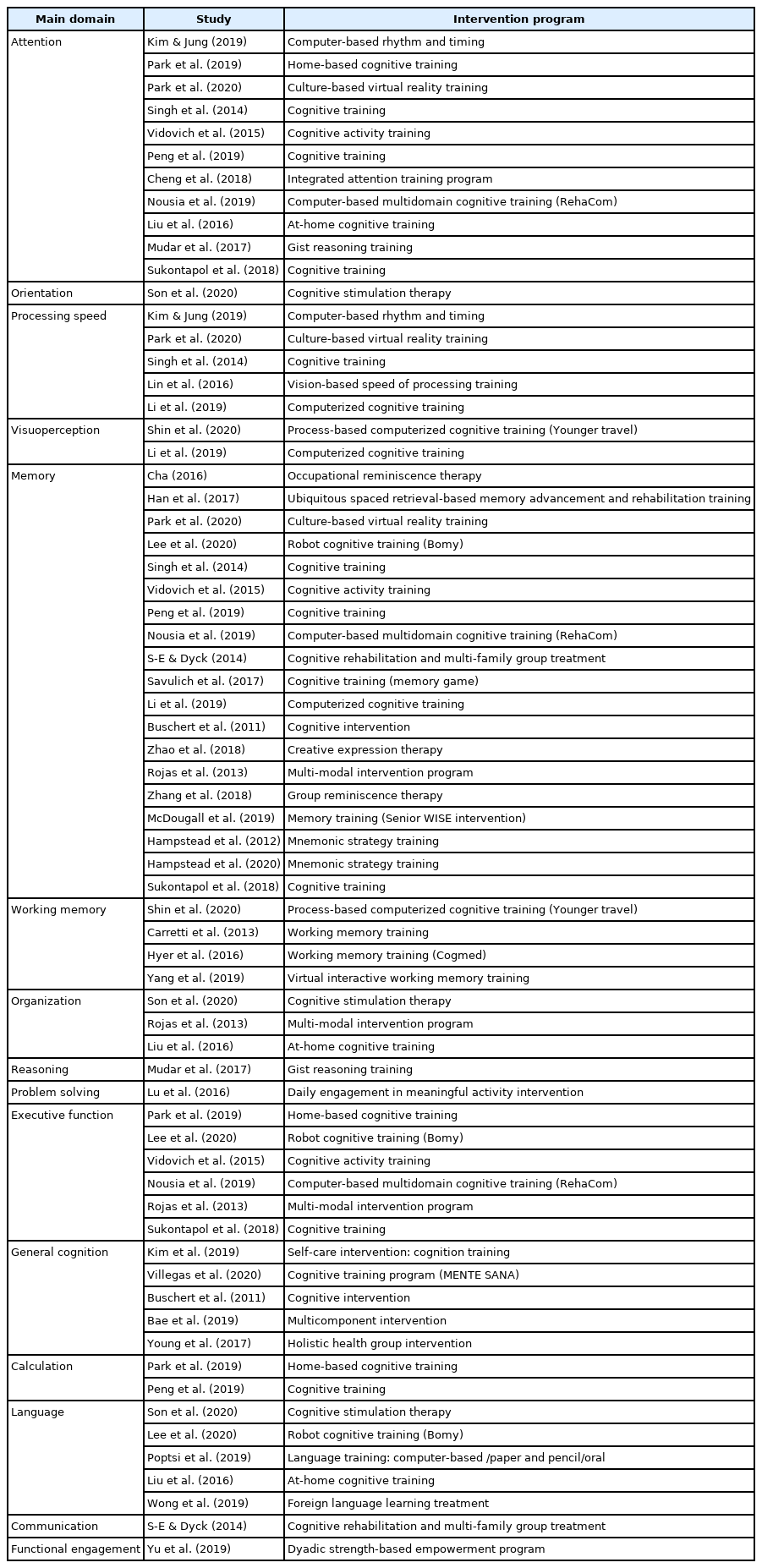

인지-의사소통 중재 프로그램은 주로 주의력, 시지각력, 기억력, 작업기억, 집행기능, 전반적 인지 등의 인지 영역과 표현, 이해, 전반적 언어 등의 의사소통 영역으로 구성되었다. 인지에 중점을 둔 중재 프로그램으로는 작업기억 훈련(working memory training), 시각 기반 처리 속도 훈련(vision-based speed of processing training), 기억 전략 훈련(mnemonic strategy training), 요지 추론 훈련(gist reasoning training) 등이 있었다. 의사소통 중심 프로그램에는 창의적 표현치료(creative expression therapy), 외국어 학습치료(foreign language learning treatment) 등이 포함되었다. 방법적 측면에서는 로봇 인지 훈련(robot cognitive training), 컴퓨터 기반 다영역 인지 훈련(computer-based multidomain cognitive training), 가정 인지 훈련(at-home cognitive training), 집단 연상치료(group reminiscence therapy) 등이 활용되었다. 실험 집단에 적용된 인지-의사소통 중재의 주요 영역 및 프로그램은 Appendix 3에 상세히 제시하였다.

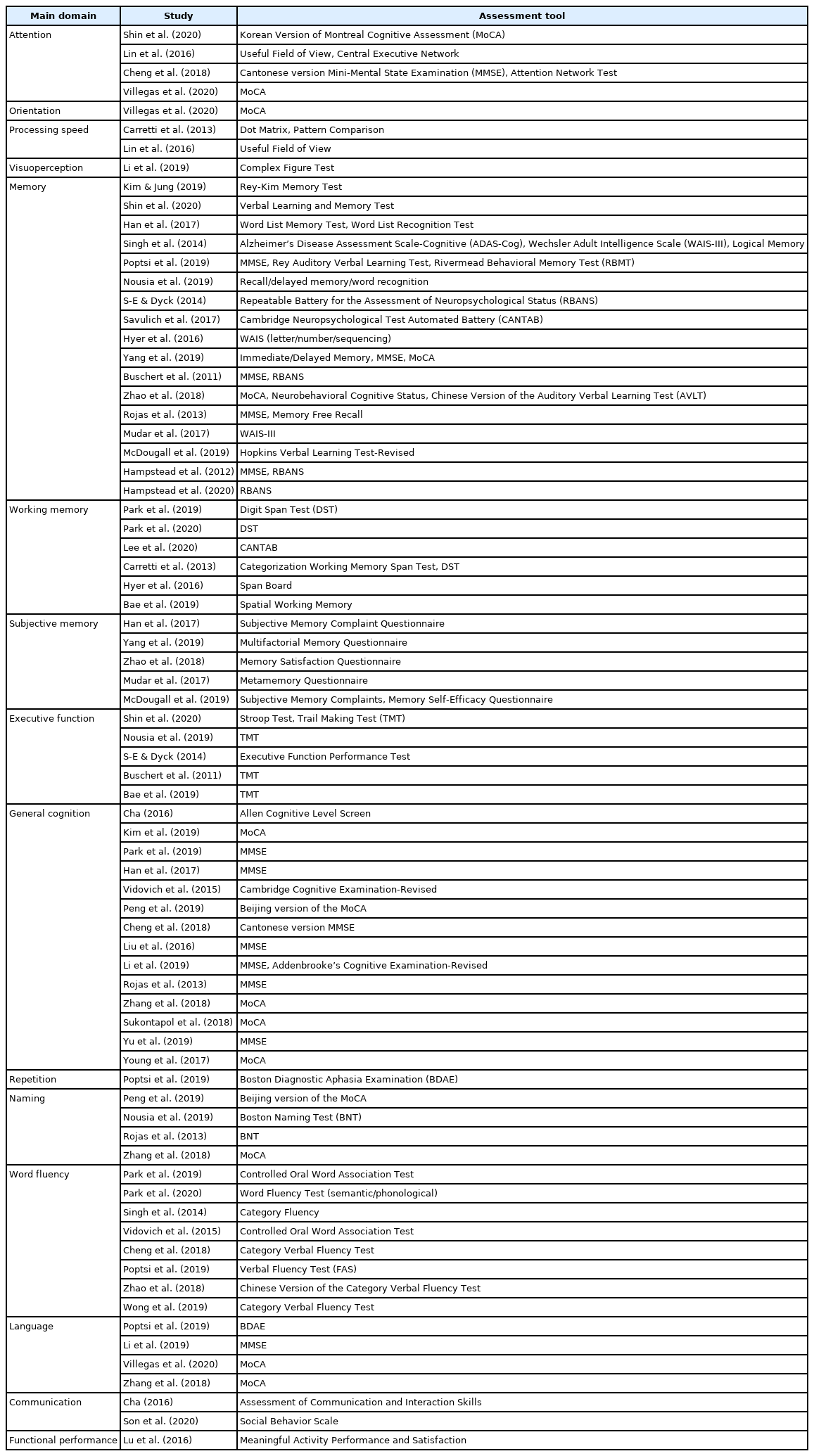

중재 결과에 대한 평가는 직접적으로 중재한 영역에 대한 근전이(near transfer) 효과 및 중재하지 않은 영역에 대한 원전이(far transfer) 효과를 제시하였다. 인지 측면에서 주의력, 시지각력, 처리 속도, 기억력, 작업기억, 주관적 기억력, 집행기능, 전반적 인지 등이 포함되었고, 의사소통 측면에서 따라말하기, 이름대기, 단어유창성, 구어/비구어 의사소통, 대화 등의 수행력이 분석되었다. 결과 평가에 빈번히 활용된 도구로는 Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Mini-Mental State Examination, Trail Making Test, Digit Span Test 등이 있었다. 기타 평가 도구는 중재 프로그램의 특성에 따라 다양하게 적용되었다. 중재 결과 평가의 주요 영역 및 도구는 Appendix 4와 같다. Appendix 5에는 분석에 포함된 전체 연구들이 제시되었다.

효과크기의 분석

평균 효과크기

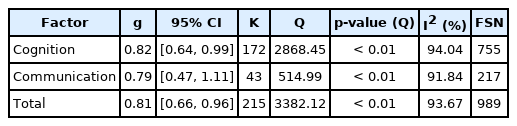

MCI를 대상으로 한 인지-의사소통 중재의 평균 효과크기를 분석한 결과, g = 0.81, 95% 신뢰구간 [0.66, 0.96]으로 ‘큰’ 정도의 유의한 효과를 나타내었다(p< 0.01). 즉 중재를 받은 집단의 인지-의사소통 능력이 통제 집단에 비해 유의하게 높은 수행력을 보였다. 세부적으로는 인지 영역 g = 0.82, 의사소통 영역 g = 0.79로 각각 ‘큰’ 및 ‘중간’ 수준의 유의한 효과크기를 보였다(p< 0.01). 인지, 의사소통, 인지-의사소통의 평균 효과크기를 분석한 결과는 Table 3에 제시하였다.

하위 영역별 효과크기

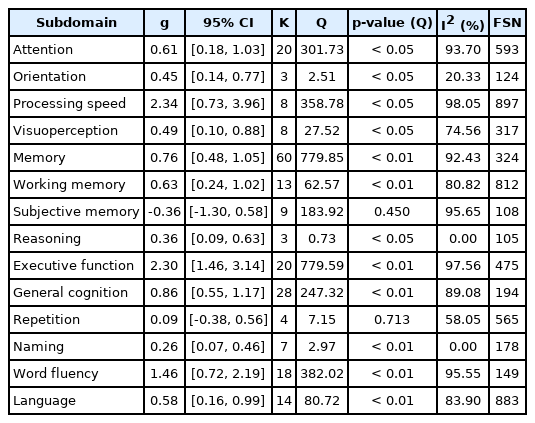

인지-의사소통 중재의 각 하위 영역별로 효과크기를 비교한 결과는 Table 4와 같다.

인지 측면에서 처리 속도(g = 2.34, p< 0.05), 집행기능(g = 2.30, p< 0.01), 전반적 인지(g = 0.86, p< 0.01)는 ‘큰’ 효과크기, 기억력(g = 0.76, p< 0.01), 작업기억(g = 0.63, p< 0.01), 주의력(g = 0.61, p< 0.05)은 ‘중간’ 효과크기, 시지각력(g = 0.49, p< 0.05), 지남력(g = 0.45, p< 0.05), 추론력(g = 0.36, p< 0.05)은 ‘작은’ 효과크기를 나타내었다. 주관적 기억력(g = -0.36, p = 0.450)의 효과크기는 유의하지 않은 것으로 분석되었다.

의사소통 영역에서 단어유창성(g = 1.46, p< 0.01)은 ‘큰’ 효과크기, 언어(g = 0.58, p< 0.01)는 ‘중간’ 효과크기, 이름대기(g = 0.26, p< 0.01)는 ‘작은’ 효과크기를 보인 반면, 따라말하기(g = 0.09, p = 0.713)의 효과크기는 유의하지 않았다.

인지 및 의사소통 영역에서 상대적으로 큰 효과크기를 보인 ‘처리 속도’와 ‘단어유창성’의 forest plot은 Figure 3 및 Figure 4에 제시하였다.

DISCUSSIONS

본 연구는 체계적 고찰과 메타 분석을 통해 MCI에 대한 인지-의사소통 중재의 효과를 제시하고자 하였다. 이를 위해 2012년 이후의 38개 국내외 연구를 대상으로 질적 특성을 살펴보고 중재 결과에 대한 효과크기를 분석하였다.

연구의 질적 분석

연구 방법의 측면에서 본 분석에 포함된 연구 대상은 중재가 적용되거나 적용되지 않은 MCI 집단이었다. MCI의 하위 유형을 세분화한 9건의 연구 중 aMCI는 7건으로 대다수를 차지하였고, non-aMCI와 4개 유형이 각각 1건씩이었다. aMCI는 ‘증후성 AD 전 단계(symptomatic pre-AD)’로 간주되어, AD에 비해 오히려 병리생물학적(pathobiology) 양상이 더 민감하게 변화하는 유형이다(Lin et al., 2016). 이로 인해 인지-의사소통적 및 기능적 독립성을 유지하기 위한 활동이 매우 큰 영향을 미친다.

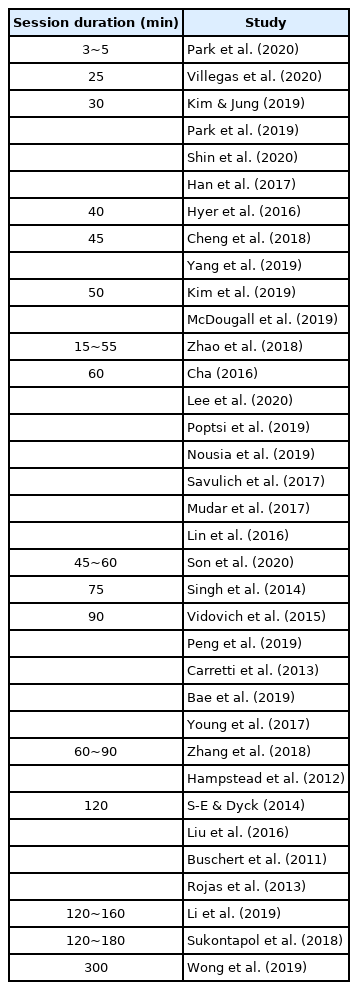

실험 집단에 적용한 중재 회기의 구성은 연구마다 상이하나, 1회기당 30~60분의 중재가 과반수를 차지하였다. 중재의 총 회기 수는 5~48회로 광범위하였다. 세부적으로 살펴보면, 회기당 시간은 60분 7건, 90분 5건, 30분 및 120분 각각 4건 순으로 많았고, 중재 회기는 주당 2~3회가 13건으로 전체 연구의 대다수를 이루었다. 총 중재 수는 5~48회기로 개별 연구에 따라 다양하였다. MCI 환자의 인지-의사소통 문제가 관계, 치료 참여, 기분, 독립성 등 일상생활에 부정적으로 작용하는 점을 고려할 때, 하위 유형 및 증상에 따른 적절한 회기의 구성은 중재 효과의 주요 변인이 될 수 있다. 반면 중재의 빈도 및 기간을 반영하는 훈련 강도의 차이가 aMCI 집단에 적용한 인지 처리 속도 및 기능적 훈련의 효과에 영향을 미치지 않는다는 보고도 있다(Lin et al., 2016). 따라서 중재 강도와 적용 결과 간의 상관성을 규명하고, 이를 효과적인 중재에 활용할 필요가 있다.

중재 내용의 측면에서 다양한 프로그램이 적용되었으나, 주요 목표로 삼은 하위 영역은 기억력, 주의력, 집행기능 등 특정 영역에 국한되는 경향을 보였다. 의사소통의 경우 전반적 언어나 기능적 의사소통을 다룬 경우가 대부분이며, 표현, 이해 등의 하위 영역에 초점을 둔 소수의 연구가 포함되었다. 프로그램의 유형 중에는 인지 훈련의 형태가 가장 보편적이었다. 이에는 자가관리(self-care), 가정 기반, 과정 기반 컴퓨터(process-based computerized), 로봇, 인지 활동, 기억력 게임, 기억력 전략 훈련 등 다양한 양식이 활용되었다. 이밖에 특정 인지 기능을 향상시킴으로써 일상생활 기능을 촉진하는 인지 자극치료, 그리고 인지적 결손에 대한 보완적 또는 회복적 중재에 주력하는 인지 재활도 일부 중재 프로그램에 활용되었다. 특히 보편적 간격-회상 기반(spaced retrieval-based) 재활, 인지 재활 및 다문화 가정 집단 치료 등이 후자의 예시에 해당하였다.

인지 훈련은 특정 영역에 대한 훈련을 통해 해당 인지기능을 향상시킴으로써 궁극적으로 인지보존 능력과 인지적 가소성을 증진하는 데 기여한다(Clare & Woods, 2004). 이는 MCI로 인한 임상적 증상을 완화하고 AD로의 진행을 예방하기 위함이다. 여러 회기에 걸쳐 소수 인원을 대상으로 전략적 훈련이나 전문 교육, 과정 기반 훈련 등을 적용하기 때문에 보편화된 중재 방법으로서 활용된다. 본 분석에 포함된 연구에서 인지 훈련 형태의 프로그램이 가장 많이 적용된 것도 이와 동일한 맥락으로 간주된다. 후기 MCI나 경도~중등도 치매 환자에게 주로 적용하는 인지 재활은 특정 영역보다는 전반적인 일상생활의 수행을 향상시키는 데 주목한다(Clare & Woods, 2004). 본 분석에 포함된 인지 재활 프로그램도 주로 기능 활동 훈련, 전략 및 과정 반복, 다감각적 중재 등으로 구성되었다.

중재 결과에 대한 평가는 크게 두 유형으로 분류되었다. 첫째, 인지-의사소통 중재를 직접적으로 시행한 영역에 대한 근전이 효과를 제시한 경우이다. 본 분석에 포함된 연구들은 주로 근전이 효과를 중재 결과로써 측정하였다. 즉 중재 프로그램의 주요 영역인 기억력, 주의력, 집행기능 등에 나타난 효과를 제시한 연구가 많았다. 의사소통 측면에서 Poptsi et al.(2019)은 컴퓨터/지필/구어 기반 언어 훈련을 통해 이해 및 표현 능력을 중재한 후 단어유창성, 따라말하기, 전반적 언어 등에 미친 근전이 효과를 제시하였다. 둘째, 직접 중재하지 않은 인지-의사소통 영역에 대한 원전이 효과를 제시한 경우이다. 예를 들어, 주의력 통합 훈련 프로그램을 통해 지속·선택·분리 주의력을 중재한 연구에서는 주의력에 대한 근전이 효과뿐 아니라 전반적 인지, 기억력, 단어유창성 등의 원전이 효과도 알아보았다(Cheng et al., 2018). Lin et al.(2016)은 시각 기반 처리 속도 훈련을 시행한 후 주의력, 작업기억, 전반적 인지, 단어유창성 등에 미친 효과를 분석하였다.

효과크기의 분석

본 분석에 포함된 모든 연구들의 평균 효과크기를 살펴본 결과 ‘큰’ 정도의 유의한 효과가 있었다. 이는 MCI에 대한 인지-의사소통 중재가 매우 효과적임을 시사하는 결과이다. 이를 반영하듯, 최근의 여러 문헌 검토에서 MCI에 대한 인지-의사소통 중재의 효과성이 보고된 바 있다(Buschert et al., 2011; Huckans et al., 2013; Sherman et al., 2017). 중재 방법이나 프로그램의 유형에 따라 상이할 수 있으나, MCI에 대한 중재가 인지-의사소통 기능과 일상생활 활동을 증진하는 데 기여하고 궁극적으로 삶의 질을 높이는 효과가 있다는 결과가 많다(Bae et al., 2019; Sherman et al., 2017). 이러한 효과는 MCI 환자 자신의 인지에 대한 인식을 의미하는 ‘메타 인지’에도 긍정적으로 작용한다고 알려져 있다(Chandler et al., 2016).

본 연구에서 인지와 의사소통 영역은 각각 ‘큰’ 및 ‘중간’ 수준의 유의한 효과크기를 보였는데, 특히 후자의 경우 일상생활 활동뿐 아니라 메타 인지 등의 고차원적 기능과 직결된다는 점에서 시사하는 바가 크다. 실제로 중재 효과를 보인 MCI 환자에 대한 뇌영상 분석 결과 백질(white matter)의 통합성과 전전 두피질(prefrontal cortex)의 두께가 증가했다는 보고가 있다(Youn et al., 2011). 최근 들어 다양식적 접근법의 개발과 적용이 강조되는 것도 이러한 기능적 효과성을 고려한 추세로 간주된다(Bae et al., 2019; Park et al., 2018).

하위 영역별 효과크기를 살펴본 결과, 처리 속도, 집행기능, 전반적 인지, 기억력 등의 인지 영역이 비교적 큰 효과크기를 보였다. 이는 본 분석에 포함된 연구들의 주요 중재 영역이 집행기능과 기억력인 점을 반영하는 결과이다. 특히 기억력 기반 중재의 전반적인 효과는 다른 접근법에 비해 높다고 알려져 있다. 신경학적 측면에서도 기억력 중재는 MCI로 인해 손상된 뇌의 보상적 통로와 연결망을 활성화하고 신경가소성을 재건하는 데 기여한다(Sherman et al., 2017). 처리 속도는 인지-언어 처리의 전반적인 효율성과 직결되므로 많은 연구에서 중재 효과가 높게 나타나는 영역 중 하나이다. 예컨대, aMCI를 대상으로 한 처리 속도 기반 훈련은 주의력과 고차원적 인지, 일상생활 기능 등에 긍정적인 영향을 미친다(Lin et al., 2016). 처리 속도의 증진이 근전이 효과뿐 아니라 원전이 효과도 촉진한다는 보고도 있다(Valdes et al., 2012).

이에 반해 본 연구에서 주관적 기억력의 효과크기는 유의하지 않은 것으로 나타났다. 이는 분석에 포함된 자료 수가 9개로 비교적 적었고, 중재 결과의 측정 면에서 기억력, 작업기억 등의 객관적 평가에 비해 주관성과 이질성이 크기 때문인 것으로 분석된다. 예를 들어, 기억력과 작업기억은 Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale이나 Digit Span Test가 빈번히 활용된 반면, 주관적 기억력은 Subjective Memory Complaint Questionnaire, Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire, Memory Satisfaction Questionnaire, Metamemory Questionnaire 등으로 매우 상이하였다. 이 같은 특성이 주관적 기억력의 중재 효과에 영향을 미친 것으로 추측된다.

의사소통 측면에서는 단어유창성, 전반적 언어, 이름대기 순으로 효과크기가 높게 나타났다. MCI 환자는 어휘 판단, 의미적 범주 및 부호화, 의미 점화(priming)와 같은 의미기억, 담화 수준의 표현 및 이해에 어려움을 보인다(Hudon et al., 2006). 특히 다영역형 aMCI는 주의력, 집행기능, 구어 및 시각 기억 문제가 언어적 결함과 연계되어 보다 두드러진다(Poptsi et al., 2019). 이는 언어 이해, 구문적 추론의 정확도, 이름대기 등 다양한 언어 수행력과도 관련된다. 따라서 어휘-의미 처리의 결함은 MCI의 가장 보편적인 증상에 해당한다. 즉 MCI 환자는 맥락에 맞는 의미에 접근하거나 보존된 의미 표상을 제대로 활용하지 못하기 때문에 의미적 단어유창성이나 대면이름대기를 수행하는 데 어려움을 겪는다(Shao et al., 2014).

본 연구 결과가 시사하듯, 단어유창성은 집행기능 등 다른 인지 처리에 고루 영향을 미친다. 예컨대, 단어유창성은 이전의 반응을 처리하기 위한 작업기억, 범주에 해당하지 않는 항목의 억제, 확산적 추론 등을 좌우한다(Poptsi et al., 2019). 특히 MCI는 AD에 비해 범주에 대한 단어유창성이 더 크게 저하된다는 보고도 있는데, 이로 인해 MCI의 조기 진단 및 예후에 매우 유용한 과제로 간주된다. 이처럼 어휘-의미적 처리는 MCI의 초기부터 결함을 보이기 때문에 다양한 의미적 표상뿐 아니라 어휘적 활성화를 크게 방해하는 요인이 된다. 본 연구에서 단어유창성의 효과크기가 가장 크게 나타난 것도 이와 동일한 맥락으로 간주된다.

요컨대, 본 연구는 MCI의 인지-의사소통 중재에 대한 체계적 고찰과 메타분석을 통해 질적 및 양적 측면에서 중재 효과를 논의하였다. 이러한 증거 기반적 검증은 MCI를 대상으로 한 중재 접근법을 다양화하고 효율적 시도를 활성화하는 데 크게 기여할 것이다. 궁극적으로 MCI의 인지-의사소통적 결함을 완화하고 치매로의 진행을 예방하기 위한 지침으로서 활용될 수 있을 것이다.

향후 연구를 통해 보완할 점은 다음과 같다. 첫째, 인지-의사소통의 하위 영역에 따라 분석된 자료 수가 3~60개로 매우 상이하다. 이는 효과크기를 비교하는 데 영향을 미칠 수 있으므로 추후 보완할 필요가 있다. 둘째, MCI의 하위 유형별로 인지-의사소통 중재의 효과가 다를 수 있다. 본 분석에 포함된 자료는 특정화되지 않은 유형이나 aMCI가 대다수이므로, 향후에는 하위 유형별로 세분화된 분석이 시도되어야 할 것이다. 셋째, 본 연구에는 데이터베이스 및 학술지에 게재된 문헌만을 대상으로 삼았다. 따라서 출판편의에 대한 검증을 거쳤음에도 ‘회색 문헌(grey publications)’이나 ‘비관행적 문헌(non-conventional publication)’을 포함하지 않은 데 따른 편향성을 완전히 배제하기 어렵다. 향후에는 이를 보완하기 위한 추가적인 고찰이 필요할 것이다.

Acknowledgements

N/A

Notes

Ethical Statement

N/A

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

There are no conflict of interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A8040953).